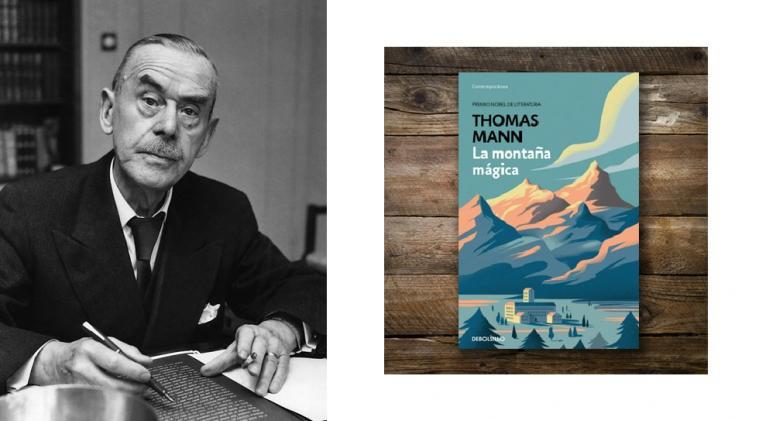

One hundred years of La montaña mágica

especiales

Now that readers claim for shorter texts, before the challeinging empire of time imposed by contemporaneity, it may be a titanic task to fully read a great novel like Thomas Mann’s La montaña mágica (The Magic Mountain).

And yet, several specialists have labeled it as one of the must-read novels in Western literature. When it comes to choose the top-100 novels of last century, The Magic Mountain is tagged in every list.

It is a very passionate and substantial work. Thus, it is paramount to overcome uneasiness when facing the length of the book.

Some of the greatest topics of artistic creation are addressed here; namely, life, death, time, sickness, and human nature, with a particularly complex narrative structure, full of symbolism.

But it does not mean we must go through overwhelming narrative or sharp images. And it perhaps has to do with the ability to create solid characters, with which readers may or may not feel identified from the clear expression of emotions and thoughts.

We are not facing a work of ruptures, Thomas Mann is embedded without trauma into a long tradition, but the writer uses with ease and elegance literary resources that marked a good part of later literature, especially the much-used interior monologue.

In the end, The Magic Mountain is an incisive recreation of European society at the beginning of the 20th century, in the tense years before the WWI.

Many of the causes of this great conflict are made explicit in the bitter debates of the characters, creatures who seem trapped in a sanatorium in the Alps, victims of respiratory conditions.

Synopsis

Hans Castorp, a 22-year-old engineering student from a wealthy family, goes to visit his cousin at the tuberculosis hospital in Davos, where his stay, originally planned for three weeks, turns into a seven-year stay. He soon understands that the logic that governs in the hospital, located at 1530 m above the sea level, is different from that of the world of healthy people.

First page

AN UNASSUMING young man was travelling, in midsummer, from his native city of Hamburg to Davos-Platz in the Canton of the Grisons, on a three weeks’ visit.

From Hamburg to Davos is a long journey—too long, indeed, for so brief a stay. It crosses all sorts of country; goes up hill and down dale, descends from the plateau of Southern Germany to the shore of Lake Constance, over its bounding waves and on across marshes once thought to be bottomless.

At this point the route, which has been so far over trunk-lines, gets cut up. There are stops and formalities. At Rorschach, in Swiss territory, you take train again, but only as far as Landquart, a small Alpine station, where you have to change. Here, after a long and windy wait in a spot devoid of charm, you mount a narrow-gauge train; and as the small but very powerful engine gets under way, there begins the thrilling part of the journey, a steep and steady climb that seems never to come to an end. For the station of Landquart lies at a relatively low altitude, but now the wild and rocky route pushes grimly onward into the Alps themselves.

Hans Castorp—such was the young man’s name—sat alone in his little grey-upholstered compartment, with his alligator-skin hand-bag, a present from his uncle and guardian, Consul Tienappel—let us get the introductions over with at once—his travelling-rug, and his winter overcoat swinging on its hook. The window was down, the afternoon grew cool, and he, a tender product of the sheltered life, had turned up the collar of his fashionably cut, silk-lined summer overcoat. Near him on the seat lay a paper-bound volume entitled Ocean Steamships; earlier in the journey he had studied it off and on, but now it lay neglected, and the breath of the panting engine, streaming in, defiled its cover with particles of soot.

Two days’ travel separated the youth—he was still too young to have thrust his roots down firmly into life—from his own world, from all that he thought of as his own duties, interests, cares and prospects; far more than he had dreamed it would when he sat in the carriage on the way to the station. Space, rolling and revolving between him and his native heath, possessed and wielded the powers we generally ascribe to time. From hour to hour it worked changes in him, like to those wrought by time, yet in a way even more striking. Space, like time, engenders forgetfulness; but it does so by setting us bodily free from our surroundings and giving us back our primitive, unattached state. Yes, it can even, in the twinkling of an eye, make something like a vagabond of the pedant and Philistine. Time, we say, is Lethe; but change of air is a similar draught, and, if it works less thoroughly, does so more quickly.

Numerous editions of The Magic Mountain can be accessed in the country's public library system. It can be downloaded for free on various internet portals.

Translated by Sergio A. Paneque Díaz / CubaSí Translation Staff

Add new comment