Progress in the Global Banking Process: Inclusion as an Unfinished Task

especiales

The widespread use of electronic payment gateways is a global trend that’s here to stay. It has even become an indicator of the level of development that society and economic processes have achieved — a vital part of the so-called digitalization of society. In simpler terms, this means that the less cash is used, the more developed a society is.

Of course, economic development involves many other factors, but the intensive creation of communication infrastructure, the expansion of e-commerce, and the mass adoption of payment gateways contribute to these leaps forward, beyond the specific technological development of each country.

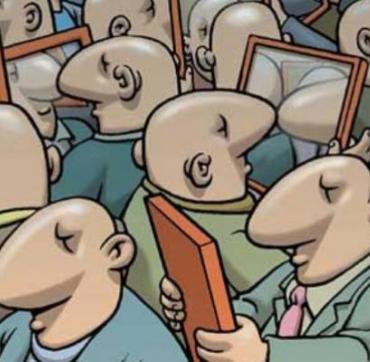

However, despite this progress, deep social inequalities — which grow exponentially in capitalist societies — are reflected in the degree of inclusion these systems achieve.

The predominantly private nature of banking systems directly influences the level of financial inclusion. Still, some countries are making strides to better integrate various digital banking services to expand their customer base.

This issue, worth repeating, is crucial for significant advancements in the digitalization process. It’s nearly impossible to expand electronic payment methods — especially in the vast commercial sector of goods and services — if each customer is tied to a different bank and there are no integrating platforms.

In developed capitalist countries, financial inclusion varies depending on the structure of the financial system and the regulations governing digital operations. Generally, there’s high interoperability between different banks, facilitated by universally accepted cards like Visa and Mastercard, as well as transaction verification and integration systems like SWIFT (1) or SEPA (2).

Nevertheless, competitive dynamics among banks often hinder smoother transaction flows. Transfers are rarely instantaneous, let alone centralized.

The most paradoxical example is seen in the United States. The widely used Zelle system — adopted by banks like Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo — allows fast transfers. However, not all banks use this service, so transactions between unaffiliated institutions can take days, practically slowing down the progress of digital processes.

The European Union, Japan, and Britain show greater progress in banking interconnection compared to the US. They use systems like SEPA or initiatives like TIPS (3), which enable instant payments regardless of bank affiliation. Japan operates the Zengin System (4), while Britain commonly uses BACS (5) for electronic money transfers, especially for payrolls, pensions, and bills.

The People’s Republic of China undoubtedly leads with the world’s most advanced electronic payment gateways. Experts rate financial inclusion in China as exceptionally high, thanks to the implementation of the popular WeChat Pay and Alipay platforms — creating an almost universal ecosystem that transcends individual bank limitations.

In Latin America, progress is uneven despite ongoing efforts toward greater financial inclusion. The most successful cases recognized early on that mass digitalization requires overcoming the prevailing private, competitive logic.

Brazil stands out with PIX, a system managed by the Central Bank of Brazil launched in 2020. It supports instant transfers and payments 24/7, involving over 800 institutions and achieving 80% interoperability by February 2025 — nearly total integration. Similarly, Mexico has SPEI (6), though it’s limited to bank account holders. Other, less widespread systems like Mercado de Pago integrate both banked and unbanked users.

Other Latin American countries, like Peru and Colombia, show more limited development. Peru’s Billetera Móvil (Mobile Wallet) has seen low adoption, while Colombia offers inclusive digital wallets, though with still modest reach.

Cuba, on the other hand, boasts some of the highest levels of banking integration worldwide — widely recognized by experts and specialized media covering financial inclusion. Notably, Cuba’s state-run banking system ensures smooth interconnection and interoperability, driven by its public ownership model, which serves all citizens equally.

Inclusion remains an emblematic issue. As seen in regions like the EU, Japan, or Brazil, supra-banking mechanisms are taking root. The question remains: how much will this challenge the sacred principle of private ownership over financial systems? Or, conversely, how much does this private nature hinder faster development?

These are the contradictions of the capitalist system — needing to facilitate the greatest possible commercial flow while simultaneously maintaining competitive dynamics between banks.

In summary, from a broader perspective, the case of inclusion in smooth, electronic payment mechanisms mirrors a problem Marxism once predicted: how property structures can hinder the development of productive forces.

NOTES:

SWIFT: Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. Connects over 11,000 financial institutions in 200 countries, enabling global financial system cooperation and efficiency.

SEPA: Single Euro Payments Area.

TIPS: Target Instant Payment Settlement.

Zengin System: A financial data telecommunications system used by Japanese banks for domestic money transfers.

BACS: Bankers' Automated Clearing Services. Handles direct debit, payroll, and other bulk payments in the UK.

SPEI: Interbank Electronic Payment System — Mexico’s real-time gross settlement system.

Translated by Sergio A. Paneque Díaz / CubaSí Translation Staff

Add new comment