Imperialist War and Feminist Resistance in the Global South

especiales

he artwork in this dossier was created by women from around the world as part of the Anti-Imperialist Feminism to Change the World (2021) and Feminist (In)Security: Women against War (2022) exhibitions organised by Capire. This media platform was created in 2021 ‘to echo the voices of women in movement, to publicise struggles and organisational processes from different territories, and to strengthen local and international references of anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and grassroots feminism’.1

![]()

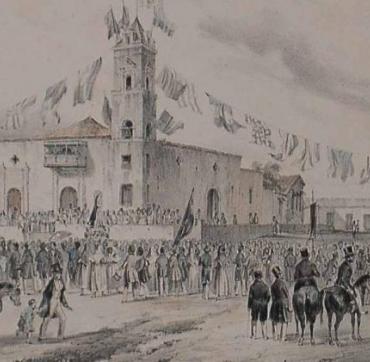

Alejandra Laprea (Venezuela), El acuerpamiento de las mujeres es nuestra estrategia de defensa (Women’s Embodied Solidarity Is Our Defence Strategy), 2022.

They say we are an unusual threat, and it is true. We are an unusual threat because we are politically educated, because we are conscious, because we don’t want to keep being [the US’s] backyard, and because we want to continue being free, sovereign, and independent.

– Ayarit Rojas, spokeswoman for the Antímano Ecosocialist Revolutionary Infantry for Habitat and Housing (Infantería Revolucionaria Ecosocialista por Hábitat y Vivienda Antímano), Venezuela.

A clear reconfiguration of global power relations has been underway since the first decades of the twenty-first century, marked by the weakening of the United States’ unipolar dominance. Its crisis of hegemony is as ferocious as its response: together with its allies in the political, military, and economic bloc that makes up the Global North, the US has tried to compensate for its loss of economic and technological power with militaristic domination.2 These countries have a shared history of violence against the peoples of the Global South, such as the genocide of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in the colonial era, the transatlantic slave trade, the use of nuclear bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people.

This exercise of disciplining and subjugating entire populations takes many forms, such as territorial occupation and militarisation, imposing unilateral coercive measures (UCMs),3 sanctions, and genocide. This unbridled phase of capitalism, in which cruelty is wielded as a form of control and domination, is what we have designated as hyper-imperialism.4

A distinctive feature of UCMs as an instrument of power is that they do not kill people directly – instead, they operate by financially, commercially, and politically isolating the targeted countries, triggering supply shortages and economic strangulation. UCMs prevent targeted countries from accessing financial resources as well as the most fundamental goods and services necessary for sustaining life, such as water, food, electricity, medicine, and medical supplies. Beyond the impact of the decreed sanctions and UCMs, there is often overcompliance by the individuals, companies, and organisations with whom impacted countries seek to establish relations, whether economic, political, or cultural. In other words, for fear of becoming the target of sanctions and UCMs themselves, these entities choose to avoid or limit their relations with the countries subject to them beyond the confines outlined by sanctions and UCMs.

This model of intervention has intensified exponentially as global disputes have sharpened. In the past two decades alone, sanctions have increased by 933%.5 The United States is leading in their application, imposing over three times more sanctions than any other country or international body (15,373 as of April 2024). These measures are inflicted upon one third of all countries, including more than 60% of all low-income countries.6 The countries with the most UCMs are Cuba, North Korea, Iran, Syria, and Venezuela.

The isolation that UCMs produce is a form of collective punishment: they are mechanisms of political control used to violently discipline and subordinate entire populations and disconnect them from global networks of commercial, financial, and political interdependence. Furthermore, UCMs are deployed alongside media campaigns aimed at stigmatising the targeted countries. In a cunning reversal, the imperialist power accuses the governments and populations affected by UCMs of being responsible for the very violence to which they are subjected. These countries are typically accused – without any evidence – of not supporting the war on drugs or fighting organised crime, of being undemocratic, etc. – and the accusation alone is enough to warrant the punishment. This reversal provides cover for the criminalisation of and discrimination against populations, leaders, and governments that do not align themselves with the interests of the hegemonic powers. These countries are targeted because they resist the neocolonial, capitalist, and patriarchal power of hyper-imperialism by working to build their own sovereignty.

UCMs are considered a strategy of ‘hybrid warfare’, ‘asymmetric warfare’, or ‘unconventional warfare’. They operate on all areas of social life – especially on the bodies, hearts, and minds of the population. They are an undeclared part of war that does not recognise borders, permeating the entirety of society and exerting control over all spheres of social reproduction and organisation.7 All studies and reports from national and international experts and UN agencies consulted for this dossier highlight that sanctions as well as UCMs disproportionately impact the most vulnerable sectors of the population – in particular, women, children, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+ people. While the lack of employment and sources of income impact the entire population, women are disproportionately impacted by the destruction and weakening of the infrastructure of social services. This process directly affects social reproduction, especially care work, which is performed almost exclusively by women. Sanctions and UCMs clearly reinforce patriarchy and other forms of social discrimination.

In 2023, the third Dilemmas of Humanity Conference took place in South Africa. At the panel ‘Feminism and Struggles against Patriarchy’, the lasting impact of imperialism on the lives of women and the LGBTQIA+ people came up repeatedly. Women from the Arab Maghreb region and Palestine described the horror of imperialist territorial occupation, the difficulty of surviving in conditions of inhumanity, the permanent threat of death and sexual violence, the collapse of health services, the cutting off of water supplies, and the consequences that these conditions have on social reproduction and women’s lives. Although they may not all face the constant threat of death from weapons of war, according to participants from Venezuela, Cuba, and other African and Asian countries, the UCMs imposed by the United States have a similar impact on women’s social reproduction and their ability to organise popular struggles and participate in political life in each territory. In this dossier, we analyse, from a feminist perspective, the economic and political impact of UCMs as imperialist mechanisms of subordination and control on women in some of the most targeted countries.

The process of engaging in dialogue with women from impacted countries involved overcoming various logistical and contextual barriers. Nonetheless, we established spaces for meaningful exchange in Venezuela, where women shared their experiences and strategies for resistance, reaffirming their commitment to sovereignty and communal life. We interviewed feminist leaders from various popular peasant and worker organisations, including the Antímano Ecosocialist Revolutionary Infantry for Habitat and Housing, the Venezuelan Housing Assembly Jorge Rodríguez Padre (Asamblea Viviendo Venezolanos Jorge Rodríguez Padre), and the Heroines Without Borders Organisation (Organización Heroínas sin Fronteras). The Simón Bolívar Institute for Peace and Solidarity among Peoples (Instituto Simón Bolívar para la Paz y Solidaridad entre los Pueblos), based in Venezuela, provided key support facilitating opportunities for connection and exchange, including in the most adverse circumstances. This process also reinforced the importance of documenting these struggles in order to advance collective resistance.

![]()

Valentina Machado and Valentina Lasalvia (Uruguay), Untitled, 2021.

Add new comment