Another Crisis in Brazil’s Amazon: Rising Crime

especiales

Brazil’s Amazon is home to almost 30 million people, most of whom live in rapidly growing cities and towns, like Belém in Pará state, which will host the COP30 climate summit next year. Many of these urban centers, like the deteriorating rainforests that surround them, are in trouble. Organized crime is increasingly contributing not only to deforestation in the region, but also to a surge of violence in Amazon cities.

Today, the region’s cities, peripheries, and hinterlands—rich in resources and rife with lawlessness—may have among the densest concentrations of criminal organizations in Latin America, if not the world. Against this backdrop, some local leaders are experimenting with promising new strategies to prevent and reduce crime and disrupt illicit financial flows.

Jobs and infrastructure have not kept up with rapid population growth. The Brazilian Amazon has registered the fastest slum expansion in the country since the mid-1980s, and over 40% of the region’s urban population lives in poverty, double the national average. The region also skews young, with a disproportionately high share of adolescents and children underperforming or dropping out of schools. Unemployment is also higher than the national average, and half of those who do have jobs work in the informal sector.

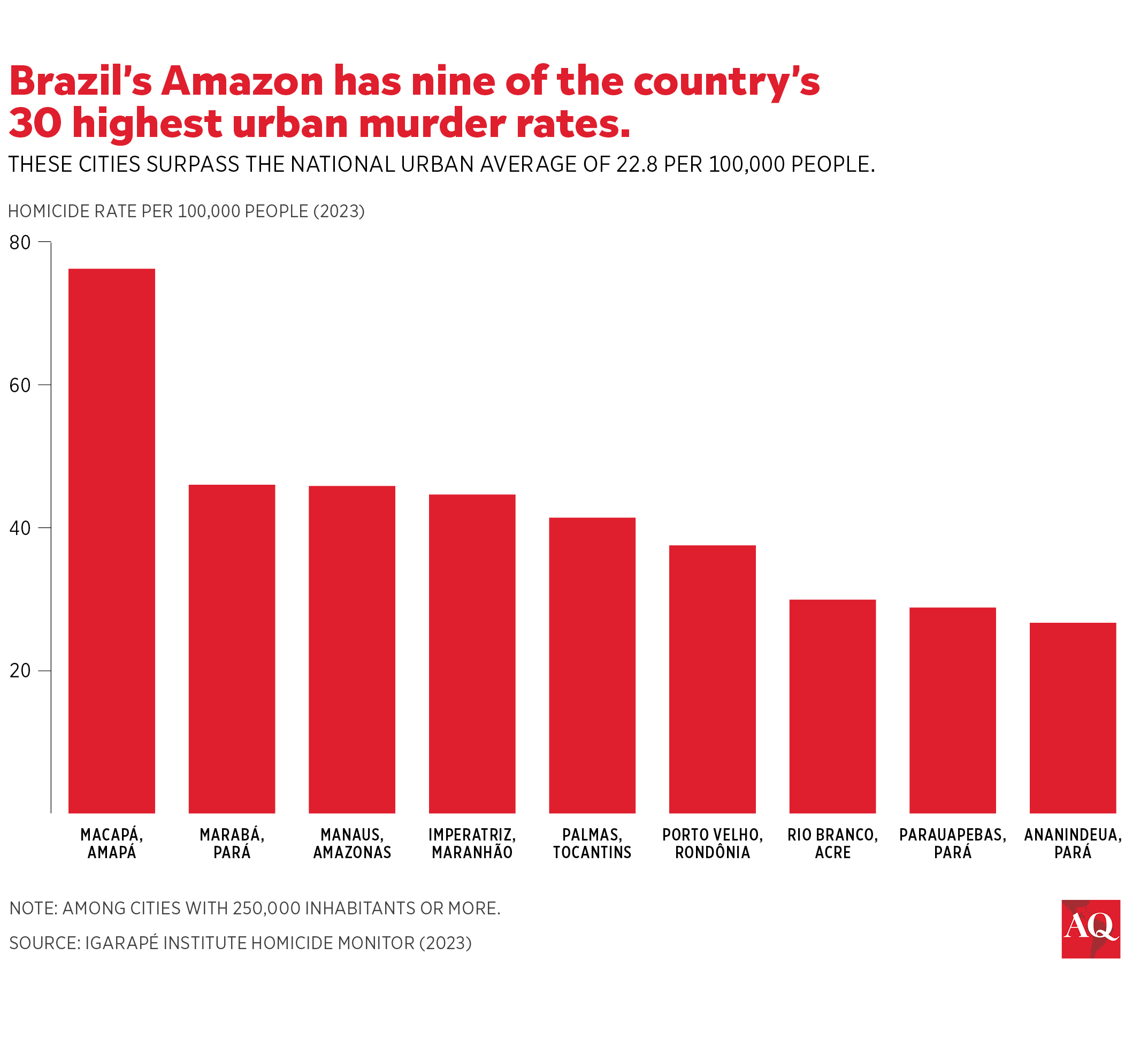

Predictably, large Amazonian cities such as Belém, Manaus, and Porto Velho are grappling with sharp increases in violent crime—but so are many of its smaller and medium-sized towns like Altamira, Ananindeua, Macapá and Marabá.

In 2023, nine of Brazil’s 30 most murderous cities were in the Amazon, with an average urban murder rate of over 34 per 100,000, 13% higher than the national urban rate. While homicide rates have declined in most of Brazil since 2017, they have continued to rise in many Amazon municipalities.

Most of the drivers of this urban violence in the Amazon are similar to those across Latin America: high rates of unemployment, inequality and impunity, along with networks of corruption, extortion and money laundering that rope in local authorities. But context-specific factors also loom large: environmental crimes involving illegal land grabs, selective logging, mining and ranching are lucrative—and intensifying land conflict, often in Indigenous territories.

Meanwhile, crime syndicates are spreading, many of them linked to transnational networks of cocaine production, distribution and retail spanning all eight Amazon Basin countries and beyond. And some of the more established organized crime groups are diversifying into new business lines, including timber extraction, gold mining and money laundering.

Brazilian syndicates like the First Capital Command (PCC) and Red Command (CV) have diffused into the Amazon from southern cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. These factions and their affiliates are recruiting locals into their ranks, especially adolescents with limited job prospects.

The region’s swelling prisons are part of the problem. Their inmate population surged 80%, from around 55,000 to 98,000, from 2012-22; among the new arrivals were gang leaders dispersed from Brazil’s five federal penitentiaries. Many of the region’s 262 state prison facilities—most overcrowded, underfunded, and hyper-violent—serve as de facto command and recruitment hubs for criminal networks.

Potential solutions

Over the past year, national authorities have stepped up measures to tackle various categories of crime across the Amazon. The Environment Ministry launched the 2023-27 Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPPCAM) and the Justice and Public Security Ministry issued an Amazon Security and Sovereignty Strategy (AMAS). The former directs additional resources to fighting environment crime, while the latter expands military and police action across 34 bases in the Amazon.

However, notwithstanding a flurry of security operations to tackle environmental crimes, including expanded funding for law enforcement from Brazil’s national development bank, there is no comprehensive national or regional strategy to improve public security and safety in the urban Amazon. One reason for this is constitutional: State governments control law enforcement and criminal justice, with cities typically less involved in the public security agenda.

Nevertheless, a handful of larger and medium-sized Amazonian states and cities are experimenting with crime prevention and reduction programs. Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon Basin with a population of over 2 million, for example, rolled out a new international police center—the CCPI—which is overseen by the federal police and focused on coordinating responses between law enforcement in Brazil, Colombia and Peru.

Meanwhile, Belém, a city of 1.3 million, is scaling up a community policing initiative called the Usinas da Paz (Peace Factories), which coordinate up to 70 free services ranging from health care and internet to educational and recreational activities. There are currently seven such factories in Belém and two in southern Pará, with another 30 factories expected in the coming years. The program is credited with significant reductions in lethal violence and crime.

Despite uneven national support, some Amazonian states, municipalities and cities are tailoring their public security strategies to address diverse forms of urban violence. Community policing models have been pursued in a handful of other Amazonian cities. For example, in the state of Maranhão, the public security secretary launched Pacto Pela Paz (Pact for Life) which promotes proximity policing to enhance the relationship between the police and the community, though its outcomes are not publicly reported.

And in the capital of Acre, Rio Branco, a Polícia da Família (Family Policing) initiative ran from 1999 to 2006. The program focused on mediating community-based conflicts and undertaking preventive interventions to strengthen safety in over 40 neighborhoods. Like other promising community policing strategies, however, it was prematurely discontinued after a change in government.

While there is growing attention to the legitimate development needs of the urban Amazon, the reality is that most of its hundreds of small, mid-sized and large cities and towns still lack the necessary plans, capacities, and resources to improve public security. This is an urgent priority, especially if Brazil intends to meet its ambitious climate and nature targets by 2030 and beyond.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Muggah is a co-founder and research director of the Igarapé Institute, a leading think tank in Brazil. He is also co-founder of the SecDev Group and SecDev Foundation, digital security and risk analysis groups with global reach.

Add new comment