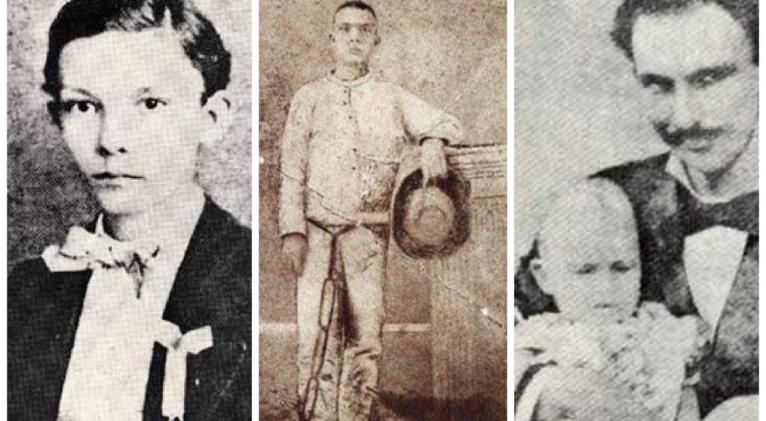

Martí as a teenager: the burden of political imprisonment

especiales

On March 4, 1870, young José Julián Martí Pérez was sentenced to six years in prison, accused of the crime of treason by the Spanish War Council that judged him, which was more repressive and dictatorial than ever in times when the Cuban mambi fighters were waging the first war for independence in eastern and central Cuba.

Since Martí was only 17 years old, he could be said to be still wearing the halo of adolescence and childhood. However, Martí was already a young man and an outstanding student encouraged by the purest patriotic and revolutionary ideals who had written the poem 10 de Octubre about the uprising of 1968 and the theatrical poem Abdala about a Nubian libertarian leader in which he is metaphorically recognized.

In the year of his trial and conviction, several testimonies reflect the existence of a suffocating repressive climate in Havana, a city apparently far from the battlefields but where patriots were already conspiring in favor of the Grito de Yara (Cry of Yara).

At that time, the so-called Havana Volunteer Corps, a reactionary and bloodthirsty paramilitary entity that tortured and killed even mere suspects of disloyalty to Spanish rule, was in full force, uncontrolled and deprived of any moral values.

On October 4, 1869, members of the said Corps thought they heard some laughter when they walked past the house of the student Fermín Valdés Domínguez, whom Martí would regularly join to study, and saw it as a mockery or provocation, so that night they decided to search the house, where they found

They found there a letter addressed to another student, Carlos de Castro, calling him an apostate for having joined the Volunteer Corps. When trying to establish who had written the note, which they seized at once as proof of a serious crime, the captors were surprised to see that both Martí and his friend Fermín claim to be responsible for it and, since their handwriting was nearly identical, it could not be determined who would take the blame.

His imprisonment was terrible ordeal. His harsh sentence forced him to wear a prison uniform—with the number 113—and work in the inhuman quarries of San Lazaro, where he would see and suffer full-fledged brutality and horror.

About this he wrote a courageous and categorical denunciation. From that time is his photograph, in prison garb, that he sent to his mother along with these painful verses: Look at me, mother, and for your love do not cry/If as slave of my age and my doctrines/Thy martyred heart I filled with thorns/Think that flowers are born among thorns.

During those cruel years, the young man not only suffered the pain in his legs and feet lacerated and infected by the iron shackles. He was also shaken by the pain of those around him, agonizing old people punished with blows and whips, and small children who could not survive in that sea of injustice and repression.

Martí would never forget the image of his father Don Mariano as the old man hugged his feet sobbing and tried to place them on some cushions that his mother had sent him to ease the pain of his sores. That was when he understood the extent of his father’s love, albeit he disagreed with his ideas. Don Mariano was an honest sergeant in the Spanish army who could not accept the pro-independence effort. His time in prison, however, brought a sort of understanding peace to their relationship.

"Infinite pain should be the only name for these pages. Infinite pain, because the pain of prison is the harshest, the most devastating of pains, the one that kills the intelligence, dries the soul, and leaves in it traces that will never be erased".

This fragment of his denunciation reveals that his feelings go beyond emotion and sentiment to become a powerful political accusation. Martí describes in detail the colonial penitentiary system and exposes the social conditions of the island, and even uses metaphors, holding that Dante’s Inferno pales beside life in the colonial prisons of the island.

It was the enormous efforts of his father that helped his sentence to be reviewed and commuted through a friend of his, the prosperous Catalonian José María Sardá, a lessor of the quarries of San Lázaro who took a personal interest in Martí and managed to change his sentence to banishment.

While recovering from his calamitous state of health, Martí spent some time in the country estate El Abra, in the then Isle of Pines, a property of the kind Sardá family. On January 15, 1871 he left Havana on the steamship Guipuzcoa, bound for Cadiz, to start his exile.

He eventually went to Zaragoza to join his dear friend Fermín Valdés Domínguez, who had served six months in prison in Havana and had been implicated in, but at some point fortunately spared from the events that ended in the horrendous murder of the medical students on November 27, 1871. On April 12, 1871 José Martí published El presidio político en Cuba through the Spanish newspaper La Soberanía Nacional.

Add new comment