Decaying Guantánamo Defies Closing Plans

especiales

Days before, Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. had called Uruguay’s president, José Mujica, pressing him to resettle the men. The foreign leader had offered to accept the detainees last January, but by the time the United States was ready for the transfer this summer, Mr. Mujica was worried that it would be politically risky to follow through because of coming elections in his country, according to Obama administration officials.

After four days of frantic negotiations between the two governments as the plane sat on the tarmac, the C-17 flew away without its intended passengers.

Although President Obama pledged last year to revive his efforts to close Guantánamo, his administration has managed to free just one low-level prisoner this year, leaving 79 who are approved for transfer to other countries. It has also not persuaded Congress to lift its ban on moving the remaining 70 higher-level detainees to a prison inside the United States.

Photo

“It’s a long way from being closed,” said Gen. John F. Kelly, the leader of the United States Southern Command, which oversees Joint Task Force Guantánamo. “Obviously the president is trying hard, he’s got people trying hard to get countries to take them, but at the end of the day, it’s going to take congressional action” to repeal the transfer ban.

More than 12 years after the Bush administration sent the first prisoners here, tensions are mounting over whether Mr. Obama can close the prison before leaving office, according to interviews with two dozen administration, congressional and military officials. A split is emerging between State Department officials, who appear eager to move toward Mr. Obama’s goal, and some Pentagon officials, who say they share that ambition but seem warier than their counterparts about releasing low-level detainees.

Legal pressures are also building as the war in Afghanistan approaches its official end, and the judiciary grows uncomfortable with the military’s practice of force-feeding hunger strikers. And military officials here, faced with decaying infrastructure and aging inmates, are taking steps they say are necessary to keep Guantánamo operating — but may also help institutionalize it.

Photo

Parts of the wartime penal colony, intended to keep detainees only temporarily, are fraying. The unit that houses the most notorious detainees is built on unstable ground — a floor is described as buckling — and will need replacement for any long-term use. In the kitchen building, temperatures soar to 110 degrees at midday, steel supports are corroded, and workers must cover dry goods with plastic tarps during storms because of a leaky roof. In the troops’ quarters, some guards are required to live six to a small shack, with poor ventilation and no attached bathrooms.

The quality of the medical facilities has also raised concerns because Congress has prohibited sending even critically ill detainees to the United States. After Latin American countries declined to take a detainee if an emergency arises, Pentagon lawyers concluded that it was lawful not to evacuate a prisoner for urgent medical treatment, according to an internal Pentagon document acquired by The New York Times in a Freedom of Information lawsuit.

To better prepare for a medical crisis, the military has instead ordered specialized doctors to be prepared on short notice to fly in with equipment. Still, there are limits to what medical personnel can do without quick access to sophisticated hospital resources.

Mr. Obama has argued that Guantánamo should be closed because of its high costs, nearly $3 million per detainee annually, and because it endangers national security; it has become an anti-American symbol of past torture and other detainee abuses. Extremists of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, who beheaded an American reporter in Syria last month, exploited those sentiments by forcing him to wear orange clothing like the garb worn by some Guantánamo’s detainees.

Photo

The Obama administration insists that the transfers to Uruguay will still occur after its election, and as many as 14 other releases could also happen by the end the year if they get approved, according to officials familiar with the process. But some said urgency is required.

“Every month counts,” said Cliff Sloan, the State Department’s envoy on detainee transfers. “The period between now and the end of the year is critical because the path to closure demands substantial progress in moving people from Guantánamo.”

Inside the Camps

The prison facilities amid this harsh landscape of sun, scrub and dust have expanded, even as the detainee population has shrunk. In 2003, about 680 prisoners filled Camp Delta, a sprawling complex with three units of open-air cellblocks and another area of communal bunks.

Today, the remaining 149 detainees live in newer buildings, and Camp Delta sits empty. To the north, the original complex, Camp X-Ray — with kennel-like cages that were used for about four months in 2002 while Delta was built — is a ghost prison, overrun by vegetation and banana rats, tropical rodents the size of opossums.

Continue reading the main story

Photographs

Camp X-Ray: A Ghost Prison

Camp X-Ray — with its kennel-like cages that were used for about four months when Guantánamo opened — is now overrun by vines, iguanas and banana rats.

Hidden in the hills about a half-mile back from the seacoast sits Camp 7, an intelligence operations center where a group of high-level terrorism suspects, like Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the self-proclaimed mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks, are imprisoned.

Last year, the Southern Command, or Southcom, requested about $200 million to rebuild that structure; to upgrade housing for the 2,000 troops participating in the prison task force; and to replace or repair other buildings, arguing that the compound was not designed for long-term use and patching up various buildings was no longer adequate.

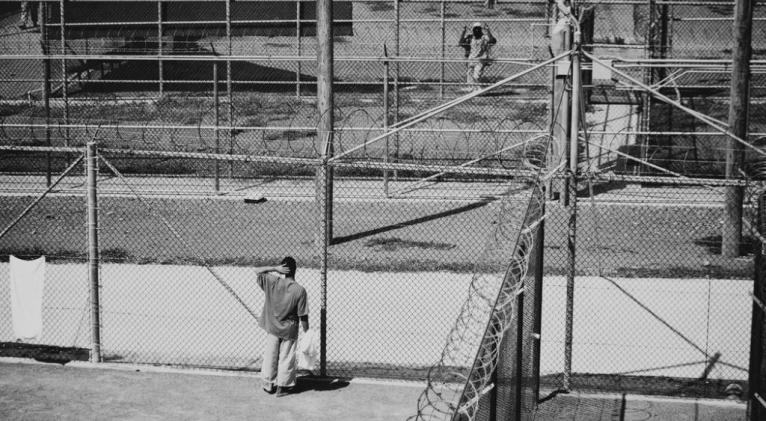

The Pentagon rejected the request, but Congress may approve about $23 million for two wish-list items: replacing the kitchen building and moving the medical clinic closer to Camps 5 and 6, concrete-walled structures where most of the detainees now live surrounded by layers of high fences covered with concertina wire.

Moreover, military officials here say they are updating a 10-year budgeting “road map” to eventually build many of the other items. They would gradually tap general military construction funds, not seek line-item approval from lawmakers in spending bills.

“We are forced to at least forecast so that we’re prepared if this detention facility is open two years from now, 12 years from now, 22 years from now, so that we’re prepared to be able to continue to do the mission,” said Rear Adm. Kyle Cozad, who took over the prison task force in June.

Continue reading the main story

The Future of Guantánamo

The Times’s Charlie Savage answers questions about the state of the Guantánamo prison today and the obstacles to closing it — or keeping it open.

Admiral Cozad argued that much of what they plan can be used even if the prison closes. That logic is designed to appeal to officials like Senator Carl Levin, the Michigan Democrat who is chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and supports closing the prison.

“Proposed spending that has a military purpose for our troops even if there are no detainees at Gitmo makes sense, but if it is needed for the detention role, then I think it is a mistake,” Mr. Levin said.

An Aging Population

Inside the main clinic, the senior medical officer recently oversaw the creation of a “Detainee Acute Care Unit” with several beds, ventilators, cardiac monitors, oxygen and other equipment. The officer, a Navy Reserve commander, is a primary care physician in the Northeastern United States. (His name was withheld under rules imposed by the military.)

Already, the doctor said, about 20 to 25 prisoners have conditions that he is monitoring, such as diabetes and high blood pressure. He expects other problems, like heart disease, strokes and cancer to arise in coming years, as with any other population that is growing older. The detainees’ average age, officials say, is 41; the youngest is 30, and the oldest is about 65.

The military has tried to build up its medical capability at Guantánamo, with mixed results. Several years ago, when a detainee needed a stent placed in a coronary artery, the military spent $1 million on a mobile cardiac catheterization lab. The prisoner ended up refusing the procedure, and the unused equipment, packed up but stored outdoors, has since decayed, officials said.

Last month, the prison temporarily imported a laser lithotripsy machine so that a visiting urologist could remove a detainee’s kidney stone — a simple outpatient procedure in the United States that became very complicated because of the logistics here. The doctor was not sure what the endeavor cost.

“You start asking, ‘Are we going to buy a laser lithotripsy machine and use it once? Are we going to buy a cath lab and sit it here just in case?’ ” he said. “These are all policy things that are way out of my lane. My job is to take the best care of them that I can.”

In Camps 5 and 6, detainees are housed according to behavior, not whether they have been designated for release or continued imprisonment. Those who comply with prison rules may live communally, eating and praying together. Up to 20 live in each cellblock, where the cell doors remain open most of the day, allowing the prisoners to mingle around a metal table or outside in a recreation yard.

Communal detainees have minimal contact with guards, but are under constant surveillance through two-way glass and security cameras. During a recent visit by a reporter, several men with long beards and short hair, wearing white and brown prison garb, stood talking in an open space. Others napped in their cells, with mats tented over their heads to shield them from the lights.

A few men sat indoors on white plastic lawn chairs, watching a television and wearing wireless headphones. Some cellblocks are designated for those who want to watch Western television and DVDs, while others are for those who want to avoid seeing women who are not covered up. Later, several prisoners put mats on the floor and prayed in the direction of Mecca.

Photo

From the roof of Camp 6, visiting journalists could see two detainees in different recreation yards, conversing in the blazing sun. A handful of detainees are attempting to grow mint, tomatoes and beans in a horticulture class, taught by a contractor who stands beyond the fence. English and Spanish classes for Arabic and Pashto speakers are also available. A life-skills class that taught résumé writing was once offered, but not enough detainees were interested, so it was replaced by lessons on using Microsoft Office, according to an officer in charge of the program.

From Plotters to Foot Soldiers

A smaller group of detainees who break the rules have fewer options for passing the time. Some are aggressive, threatening guards or trying to splash them with their urine and feces. Others protest passively, participating in a hunger strike or refusing to obey orders. These men are housed in single cells in Camp 5, where young enlisted troops peer into the windows every few minutes, 24 hours a day.

One specialist, selected by his supervisor to be interviewed, works the night shift. He is 21 years old and from Ohio; he was a third grader on Sept. 11, 2001. Asked what he thinks of Guantánamo, he said it is a place where “people who were doing the wrong thing, killing Americans, running operations” are held.

In fact, the detainees vary widely. A few, like Mr. Mohammed, are indeed senior operational Qaeda leaders tied to killing Americans. He and 14 other “high-value” detainees — who were sent to Guantánamo in 2006 from C.I.A. “black-site” prisons where some were tortured — live in Camp 7.

Much about Camp 7, which is off limits to reporters, is secret. But a 2009 military report described it: The walls of the 86-square-foot cells were designed to prevent conversation or contact with neighbors, and detainees cannot make phone calls or join classes.

Mr. Mohammed and four others accused of aiding the Sept. 11 attacks have been undergoing protracted pretrial hearings in the military commission system. Its chief prosecutor, Brig. Gen. Mark S. Martins, recently extended his tenure for three years in an attempt to see the case through, officials said.

But about half of the inmates who are detained, according to a 2010 interagency review group report, were probably just foot soldiers helping the Taliban fight the Northern Afghan militias. The report said they “lacked a significant leadership or other specialized role,” were “uneducated and unskilled” and “typically received limited weapons training.”

Photo

This group violated no law and make up the bulk of the 79 recommended for transfer if security conditions can be met. But they generally come from countries too unstable for Congress’s transfer restrictions. Fifty-eight are Yemenis. Although the United States last month repatriated two Yemeni detainees who had been held in Afghanistan, where the restrictions do not apply, officials are talking with other countries about resettling their Guantánamo counterparts.

This summer, a new warden, Col. David Heath, took over the guard force here. He gave detainees who were relatively well behaved but not yet eligible for communal conditions — it takes 90 straight days of compliance — eight hours of recreation time a day, up from two.

“That was a change I made following Ramadan, just to show them there is a new camp commander here, and I do things a little bit differently,” he said.

Transfer Attempts

Colonel Heath’s predecessor presided over a period of greater turmoil. After a two-year lull in which no low-level prisoners were released, the detainees in early 2013 began a widespread hunger strike.

The protest prompted Mr. Obama to revive his effort to close the prison. He appointed Mr. Sloan, a former White House and corporate attorney, and another envoy to negotiate transfer deals.

Photo

By law, the defense secretary has the final say on whether it is safe enough to release a detainee. Leon E. Panetta, the former defense secretary, approved no low-level transfers, but his successor, Chuck Hagel, approved 10 by December and another early this year.

By March, the details had been completed with Uruguay to take the six men — four Syrians, one Tunisian and one Palestinian. It would be the largest group to leave since 2009. No prisoner has been resettled in South America, and news of the deal inspired similar talks with Brazil, Chile and Colombia, according to regional news reports. Meanwhile, the details of separate proposed deals to repatriate four Afghans and a Mauritanian were completed in March. Momentum appeared to be growing.

But month after month passed, and Mr. Hagel did not act on the pending deals. He consults several national-security agencies when analyzing them, and some advisers, including Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, have raised concerns about whether host countries can fulfill promises to keep watch on former detainees, according to officials familiar with the deliberations. General Dempsey declined to comment.

Of the 83 detainees transferred under Mr. Obama, five have participated in terrorist or insurgent activity afterward, and two others are suspected of doing so, according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. In May, the White House sent Mr. Hagel a memo saying he should accept more than “zero risk” because allowing the prison to remain open raised risks, too. But Mr. Hagel told The Times that he was taking his time.

“My name is going on that document,” he said. “That’s a big responsibility.”

Mr. Hagel finally notified Congress in early July that he had approved the Uruguay deal, setting off a 30-day waiting period under the transfer restrictions. That led to Mr. Biden’s call and the C-17 flight to Guantánamo, to be ready if Mr. Mujica gave the go-ahead. But he instead delayed the deal.

The administration did not observe the waiting period in May, when it sent five high-level Taliban detainees to Qatar in a prisoner exchange for Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, America’s only prisoner of war from the conflict in Afghanistan. Mr. Hagel said he was satisfied with the Qataris’ security assurances, but argued that delaying the transfer would put Sergeant Bergdahl’s life at risk.

House Republicans retaliated by voting to forbid transferring any Guantánamo detainees anywhere, although that may not become law. Sharp tensions remain.

“I don’t see any support in the House for relaxing the current restrictions, or backing off our ban, in light of the president’s recent violation of the law,” said Representative Howard McKeon, the California Republican who is chairman of the House Armed Services Committee.

Still, Mr. Sloan argued that it is possible the politics could change if most of the low-level prisoners can be transferred. Relocating a population of less than 100 to a domestic prison would be a smaller problem, he said. And reducing the number of detainees would cause the expense of Guantánamo per detainee to soar further.

Taxpayers are spending about $443 million on the prison in 2014, including the cost of flying legal teams here for every commission hearing. Housing a federal inmate in a domestic maximum-security prison costs far less, $30,280 in 2013, according to the Bureau of Prisons, although that does not include court costs.

Legal Scrutiny

Meanwhile, the government is bracing for a wave of new habeas corpus lawsuits after combat operations in Afghanistan come to an end in December, raising the question of whether the legal basis for wartime detentions — the 2001 authorization to use military force against the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks — has expired.

J. Alan Liotta, the top Pentagon detainee affairs official, said that he expects the detention authority to remain viable because most detainees are considered part of Al Qaeda or an associated force, rather than solely Taliban, and the broader armed conflict continues.

Photo

Still, law of war detention was designed for a conventional conflict that comes to an end after several years. In a recent order, Justice Stephen G. Breyer took the unusual step of noting that the Supreme Court has not been asked whether the law “limits the duration” of indefinite detention in the more open-ended war against Al Qaeda.

There are signs of judicial impatience. In February, an appeals court ruled that judges may oversee the conditions of confinement at Guantánamo, and a district court judge is now examining the military’s procedures for forcibly feeding hunger strikers by restraining them and inserting gastric tubes through their noses. An official said that 11 detainees currently have lost enough weight to be “eligible” to be force-fed, though some have opted to drink a nutritional supplement when ordered.

Colonel Heath, the new warden, said he was “not intimidated” by the prospect of increasing judicial scrutiny over prison procedures. Meanwhile, he said, he intends to maintain routine for all the detainees to keep the days passing smoothly.

“I don’t spend much time thinking about who might be released or won’t,” he said. “I try to treat them all the same as much as I can; ‘fairly and consistently’ is what I preach to all my guys, because they notice variations. They’ve been here a long time.”

Add new comment