Anniversary 150 of the first José Martí political work

especiales

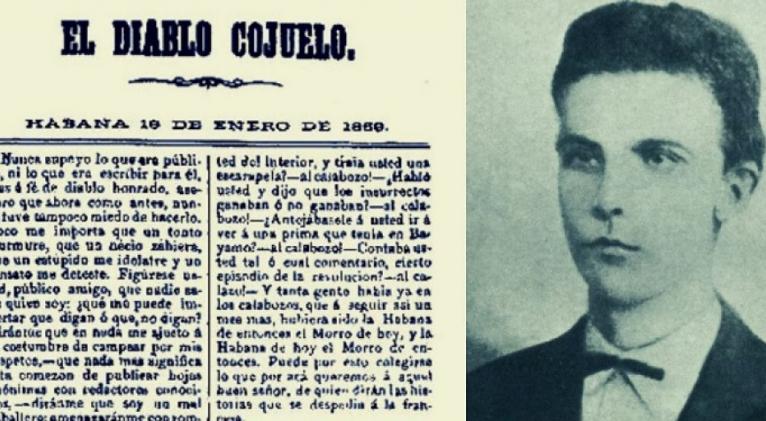

In January 19th of 1869 it was printed in Havana, in the El Iris Printer’s and Book Store located in Obispo Street, 20 and 22, the unique edition of El Diablo Cojuelo in which it was published the first political work written by José Martí when he was near to turn 16 years old.

El Diablo Cojuelo was a kind of handbill printed by Martí and his friend Fermín Valdés Domínguez. Its name had relation with the namesake novel of Luis Vélez de Guevara, Spanish writer of the XVI Century.

In the quoted work the young Martí reflected some appraisals around the situation that Cuba suffered under the Spanish colonial domain. Several months before, in October 10th of 1868, in the Eastern zone of the country the war for the independence leaded by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes already have been begun.

In the initial part of this work in El Diablo Cojuelo, Martí reflected around what write to others meant to him. Regarding this he expressed: “I have never knew what the audience was, he specified-, neither what it was to write for it, however to honest devil faith, I assure that now as before, I was never afraid of do it either.”

El Diablo Cojuelo was published taking advantage of the freedom of printing that the General Captain of Cuba Domingo Dulce y Garay who had replaced Francisco Lersundi several days before, established by decree in January 9th of 1869.

Precisely in the work that he published, Martí expresses his opinion about this theme when he detailed: “This lucky freedom of printing, that due to the waited and denied and now conceded, rains over the wet, it allow that you talk everything what you want, but not about what itches; but it also allow that you go to the Court of to the Prosecutor’s office and from the Court of to the Prosecutor’s office they duck you into the Morro because of what you said or wanted to say”.

And he added later: “But, taking back to the question of the freedom of printing, I must remember that it is not so wide that it allows to say everything what it is wanted, or publishing everything what is heard.”

In El Diablo Cojuelo by mean of small dialogues, some of them loaded with certain irony, Martí lashes the Spanish colonial regime and his representatives in Cuba.

Even he also criticizes the submissive position assumed by the publications already established and with a great power as it was the case of the Diary of the Mariana. In relation to this newspaper he affirmed: “The Diary of the Mariana has disgrace. What it advices for good thing, is justly what we all have as the worst. And this is proved by “El Fosforito”.

“What he condemns for bad, is justly what we have for good. And this is proved by me. He wanted censor, there is no censor. He said that the freedom of printing brought many bad things. For him yes, for the others no, because the one who writes wins, due to he can write, the one who prints wins, due to there is no censure that takes his job away and the one who reads wins, due to he feeds of the good things and learn to reject the bad ones, Poor Devil!”

In relation to this Martí’s first journalistic political work and the historical context in which it is published, the journalist, professor and researcher of Spanish origin, settled in Cuba since 1939, Herminio Almendros Ibáñez detailed: “It passes the year 1868, and in October 10th, in the Eastern region of the Island, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes has risen up with a group of brave men in war against Spain “which governs the island of Cuba with a bloody iron arm”.

“The war actions of the rebels in the field after the Shout of Yara for the independence cause deep impression in the cities. Teachers and students from the San Pablo school are agitated of excitement. Mendive inspires the patriotic ardor. His poems of criticism and insurgence are read and recited. Martí and his teacher sometimes follow the march of Céspedes' uprising, both alone very late at night, and the desire for freedom grows with enthusiasm in them.

“In this epoch the ideal reason that will be the course of his life to death, has already curdled in the heart of the young Martí. He will live forever consecrated to the great revolutionary effort that would make free his Homeland.

"It is not enough for the young student to admire his teacher and the elderly people who at protests show their love for their Homeland; he, in his youth of sixteen years already enters in action. In El Diablo Cojuelo, a printed sheet of paper that has been prepared with his friend Valdés Domínguez, he writes notes of ridicule and censure of the authorities and the policy, and in Free Homeland, a newspaper from which only one edition was published, that he prepares with works of Mendive and other adult people, his dramatic poem Abdala was published. The drama is like a reflection of the oppressed Cuba, and there is in it a hero who fights for the Homeland’s freedom and he dies for it.”

With the passing of time, José Martí used the journalism to reflect the engagement that he had with the liberation of his native country and also for dealing with different themes. He founded and leaded several publications.

During his stay firstly in Mexico, between 1875 and 1876 and later in the United States, from 1880 and in Venezuela, in his short settle of something more than six months in 1881, he maintained a productive cooperation with different newspapers and magazines.

Already in the final stage of his existence, when he worked in order to achieve the restart of the fight for the independence of Cuba, he precisely created a newspaper identified as Homeland, which constituted an essential stage in the divulgation of the revolutionary ideas.

Add new comment