Opinion: Culture and Revolution

especiales

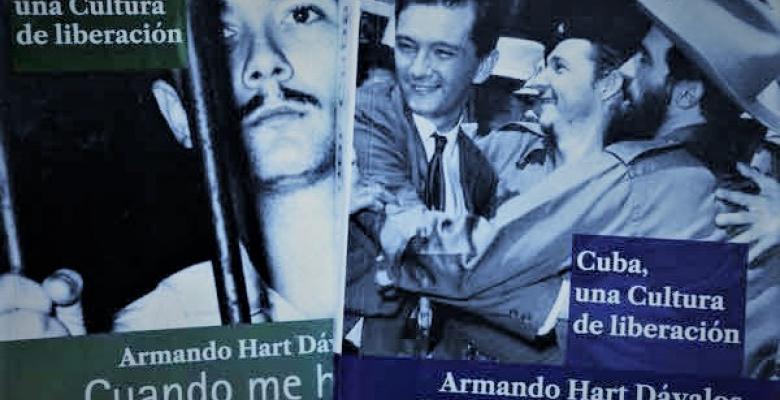

I met Armando Hart in his final years as Cuba's Minister of Culture, specifically in 1994. Those were challenging times. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union, where thousands of young Cubans had studied, triggered an economic and ideological crisis on the rebellious island. Cuba persevered. Hart actively sought out young people, encouraging dialogue with them. When he learned that a group of friends dreamed of founding a revolutionary thought magazine, he promptly summoned us, not once, but multiple times. Thus, Contracorriente was born.

Hart was a force of nature, a whirlwind. Even when seated, listening attentively, his leg would bounce restlessly, and a stubby pencil would twirl in his left hand. He was a constant generator of new ideas, a man deeply loyal to Fidel Castro. He once said that his life was divided into two periods: before and after meeting Fidel. His rapid evolution following the Moncada Barracks assault, his friendship with Frank País, and his unwavering commitment to the ideals of José Martí, which gradually integrated with Marxism, shaped him into a steadfast revolutionary. This evolution is vividly and profoundly captured in his book Aldabonazo (1997), which I highly recommend. The book narrates and explains the "natural" demise of traditional bourgeois political parties, which were unable to break free from the system's constraints and connect with the people's needs. Years later, in 2005, he wrote about the 1940 Constituent Assembly, a paradigm shattered by Batista's coup:

"That assembly was the product of a balance between two weaknesses: the old order, which lacked the strength to impose itself, and the Revolution, which also lacked the power to advance its interests. Taking a further step would have meant paving the way for a socialist program."

Hart quickly understood that the 1952 military coup catalyzed the crisis of the neocolonial Republic, a crisis not of legality but of legitimacy. His support for Contracorriente included exclusive contributions. I recall with particular gratitude two pieces: the publication of a previously unreleased letter from Che Guevara, written from Africa, discussing the study of Marxism; and a reflection titled "The Return of Marx" (1997). On one occasion, Hart recounted someone calling the Cuban revolutionaries "castaways." He retorted, "Castaways swim toward solid ground; we are the ones who best understand the causes of what happened and have the most to tell."

Unlike the socialist states of Eastern Europe, Cuba had a prior anticolonial and anti-imperialist history that underpinned its struggle, bolstered by the legacy of José Martí, who had inspired Cuban communists from Julio Antonio Mella to Fidel Castro. Consequently, the ideological battle of the 1990s in Cuba centered on this exceptional figure: Martí was the essential antecedent. The centenary of his death in combat was commemorated, and just as in 1953, during the centenary of his birth, Martí returned to reclaim the historical significance of Cuba's struggles for independence and justice. Hart was a champion of this battle. At the 1995 International Conference "José Martí and the Challenges of the 21st Century" in Santiago de Cuba, he expressed ideas that remain fundamental:

"We are defending the utopia that humanity needs today to save itself from the inferno of a civilization where, following the dramatic events symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the most ferocious and vulgar materialism has prevailed in the East and West, North and South."

He later added:

"There is no civilization without ethical culture and moral and cultural paradigms. Here in Santiago, I point out with anguish that humanity must find new paradigms, or it will be lost."

The counterrevolution also attempted to claim Martí, as every political project requires a supporting tradition, but it failed. It then sought to "kill" him by diminishing his legacy. Some recurring arguments included: a) Martí, as a poet, lived "in the clouds" and constructed a fictional Republic; b) Martí, as a thinker, was anti-modern and utopian; c) Martí was "responsible" for the Cuban Revolution (a claim that, from the right, aligns with Fidel's assertion that Martí was the intellectual author of the Moncada). It was also suggested that Cuba was abandoning Marxism to take refuge in Martí. Nothing could be further from the truth: while not a Marxist, Martí's thought aligns remarkably with Marx's in its solidarity with the world's poor, its anti-imperialism, its internationalism, its militant ethics, and its understanding of culture's role. To claims that Martí was an "idealist," Hart responded:

"The Apostle carried more realism in his verses, his prose, his fervent fight for independence, his reverence for beauty and decorum, his anti-imperialist predictions, his analyses of Latin America's problems, and his descriptions of the customs and life of the United States and other countries than the most documented and practical men of his time."

Armando Hart, heir to Cuba's finest traditions, was an educator and a man of culture. He coordinated the National Literacy Campaign as the youngest minister of the Revolution under the Ministry of Education, a mass movement that not only taught the illiterate to read but also educated the educators, revealing to urban youth the realities of rural Cuba. He often noted that, in Cuban history, the artistic and political vanguards had largely coincided. "The struggle for bread and freedom," he wrote, "must be united with the pursuit of higher spiritual development." This was a distinguishing feature of Cuba: "The identity forged in Cuba since the 19th century between culture and revolution is one of the country's most significant contributions to people's struggles for freedom."

Hart founded the Ministry of Culture to transform the relationship with artists and intellectuals after a difficult period. He understood that he was not creating an administrative body but a promoter of culture. "I always defended the idea that culture is promoted," he wrote, "and that hierarchies and roles are defined through social practice, far from bureaucratic dictates." He later established the Martí Program Office and the José Martí Cultural Society with a group of Cuban intellectuals to preserve the unity of the Homeland. He served as vice president of the National Commission that, with dozens of initiatives, commemorated the centennials between 1995 and 1998, defining years for our nation. Commander Almeida was the first vice president, and I, among giants, served as secretary. Alongside Hart, I explored the geography of Cuba's victories and defeats, and like him, I fell in love with Cuba.

Armando Hart would be 95 years old today. Though he is no longer with us physically, his words sometimes feel freshly spoken: "Fascism is in plain sight. Let us stop it. Now, more than ever, we must counter it with the formula of triumphant love and work together, all of us who feel like children of what was called the New World, to prevent the hegemony of those who hate and destroy." He said this in 1995, in Santiago, before the Apostle's tomb.

Translated by Sergio A. Paneque Díaz / CubaSí Translation Staff

Add new comment