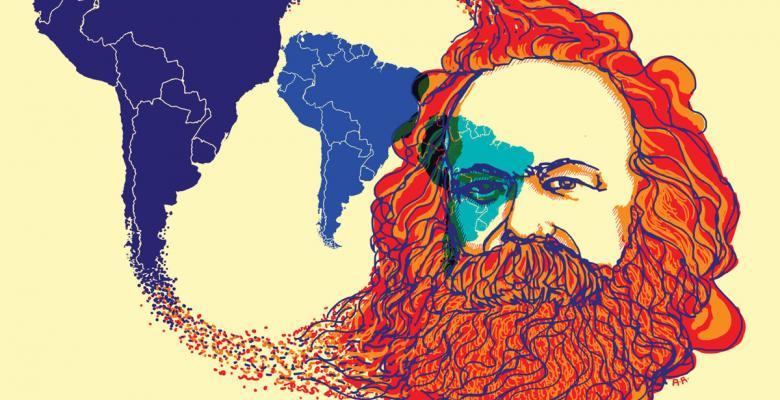

The Marxism We Need

especiales

International meetings often bring surprises. At one of them, some time ago, I met a former classmate from the University of Kiev. Yes, I studied philosophy and lived in Soviet Ukraine for five years. My classmate was a diligent, intelligent student, and he easily learned Spanish from the Cubans. He was not a member of the CPSU, but the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the capitalist direction taken by its former republics led him to join one of the communist parties that emerged later. Since then he has been an active defender of the Cuban Revolution. We’ve met more than once, in Havana and Caracas, the two centers of the Latin American revolution. But when we talk, the philosophical categories planted by Lenin seem to float without nourishing roots in the conversation: not all the statements or positions heard in flight can be defined as idealist or just materialist (sometimes, it’s not even what matters), nor are all those who defend conservative positions comfortable bourgeois or proto-bourgeois clinging to material interests.

The cultural war kidnaps the naïve, the unprepared; sometimes it even drowns those who know how to swim best. Today's world is as complex as yesterday's, perhaps as always, but it changes faster. Marxist philosophy runs after events, barely managing to catch up with them. It won’t do so from the old cabinet; nor, however modern it may seem (the word modern already seems out of date to me), from the infinite world of Internet and its networks. The most important philosophical problem remains how to transform the world, and contrary to what seems inevitable, how to outwit the form, to make the content prevail. New technologies, which are no longer the ones that prevailed just five years ago, bury us in idleness. And they fill our minds with unnecessary or false data and hypotheses that are dazzling like neon lights. That is, attractive and easy to consume, but ephemeral and misleading. The truth, before, now and later, is in the street, with the people, it’s what directs, prepares and defends people.

“Positivist” Marxism —useless and essentially reformist— is not only the manual and simplifying one of the Soviet era; it’s also the paralyzing one that, protected by the data of reality, and in the security of “two plus two equals four,” is satisfied with “what’s possible,” pretends to go far and stays close, promises profound changes and remains on the verge. Being a Marxist, I insist, is not knowing every word, every text of Marx or Lenin, or any other thinker after them; it’s knowing how to use this theoretical and practical instrument to transform the world in favor of the humble. It’s being a revolutionary. José Martí, who was a voracious reader and an insatiable connoisseur of all the avant-garde theories of his time, wrote: “It’s the human torment that in order to see well one needs to be wise, and forget that one is wise.” The solution to the war between NATO and Russia will not be, —as my friend would have wished, as Lenin understood possible in other historical circumstances for Tsarist Russia involved in the First World War— the socialist revolution in the contending countries. Not being pleased with what’s possible does not mean ignoring it; it’s about never losing sight of the horizon, contemplating the scene from above, because looking at ground level does not allow one to identify the paths or to know who are friends and foes.

It has been more than forty years since I set foot on Ukrainian soil, since I have seen the majestic red building that housed the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Kiev, and since I have not shuffled my feet among the dry, yellow and red leaves that carpet Taras Shevchenko Park in autumn. In its classrooms, young people from all the Soviet republics, from Eastern Europe, but also from Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Latin America and Africa studied. The brotherhood of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples seemed to be enshrined in the monument to Bohdan Khmelnitsky, the Ukrainian Cossack who sealed a pact of unity with Tsar Alexis I of Russia in 1654. My friend, born in Kiev, does not consider himself Ukrainian or Russian. When I ask him, he answers: “I am Soviet.”

But I want to remember this brief ironic poem by Roque Dalton:

Little letter

Dear philosophers,

dear progressive sociologists,

dear social psychologists:

do not fuck so much with alienation

here where the most fucked up

is the foreign nation.

Translated by Amilkal Labañino / CubaSi Translation Staff

Add new comment